Sculpting Light

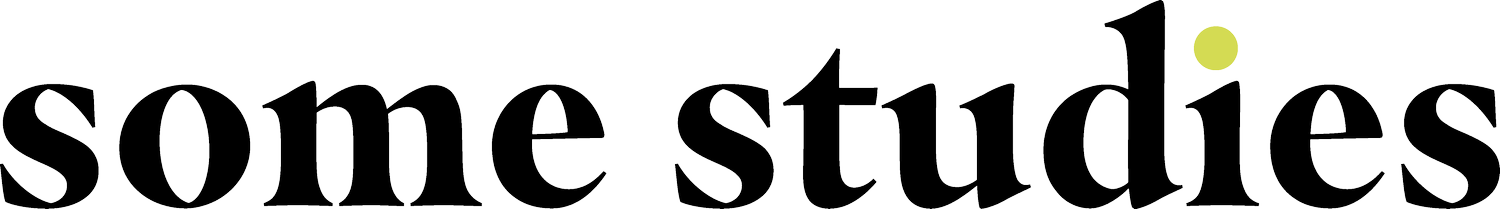

Isamu Noguchi working on Akari in Japan, 1968. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

Source: Artsy

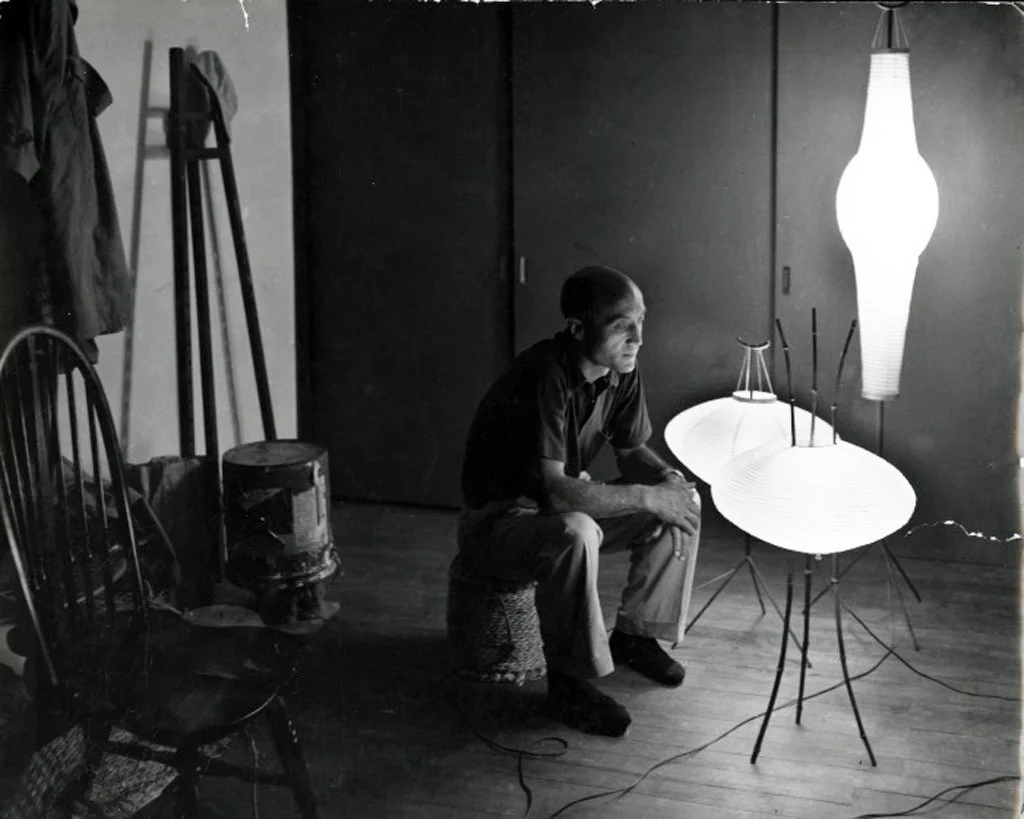

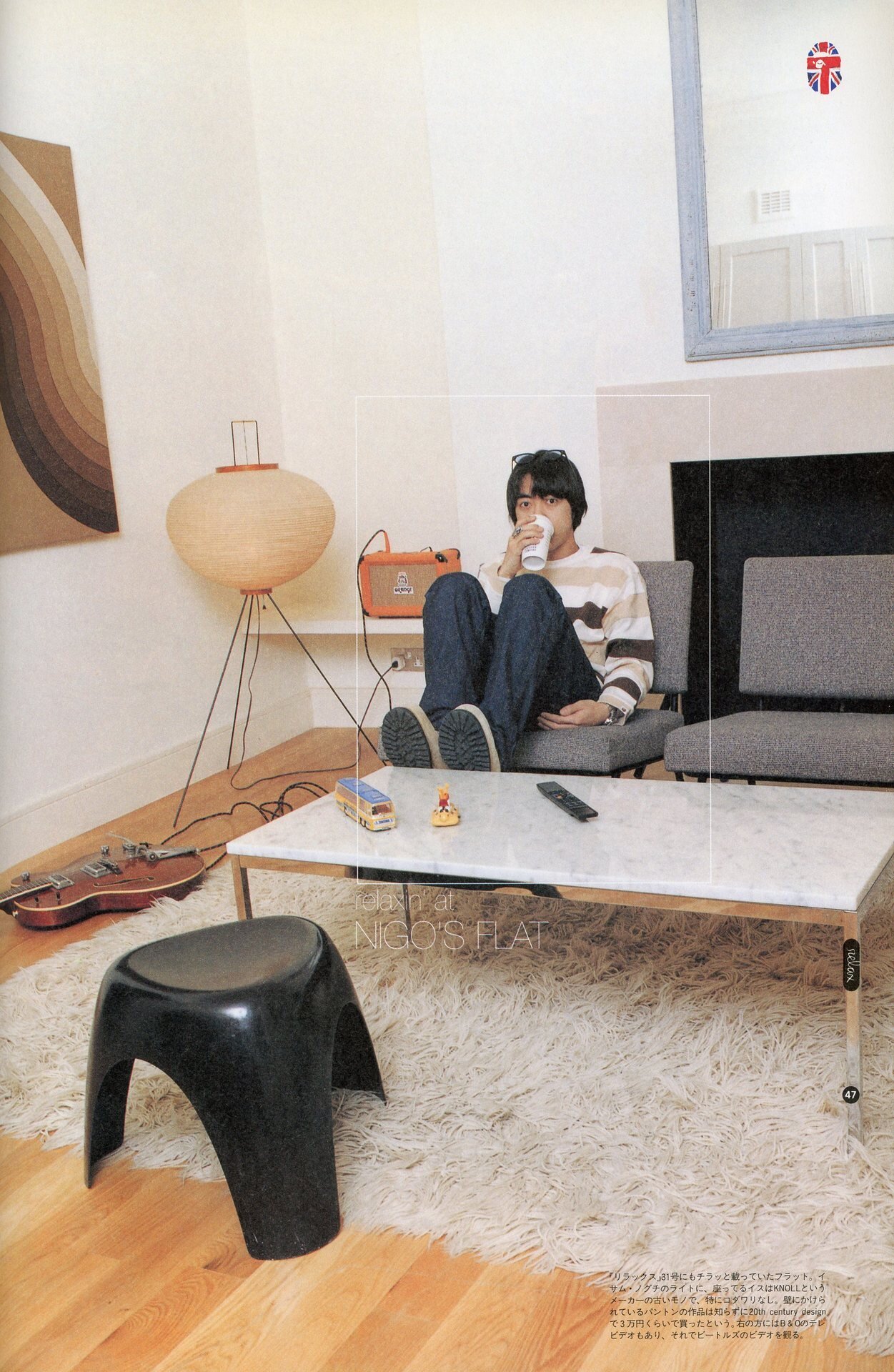

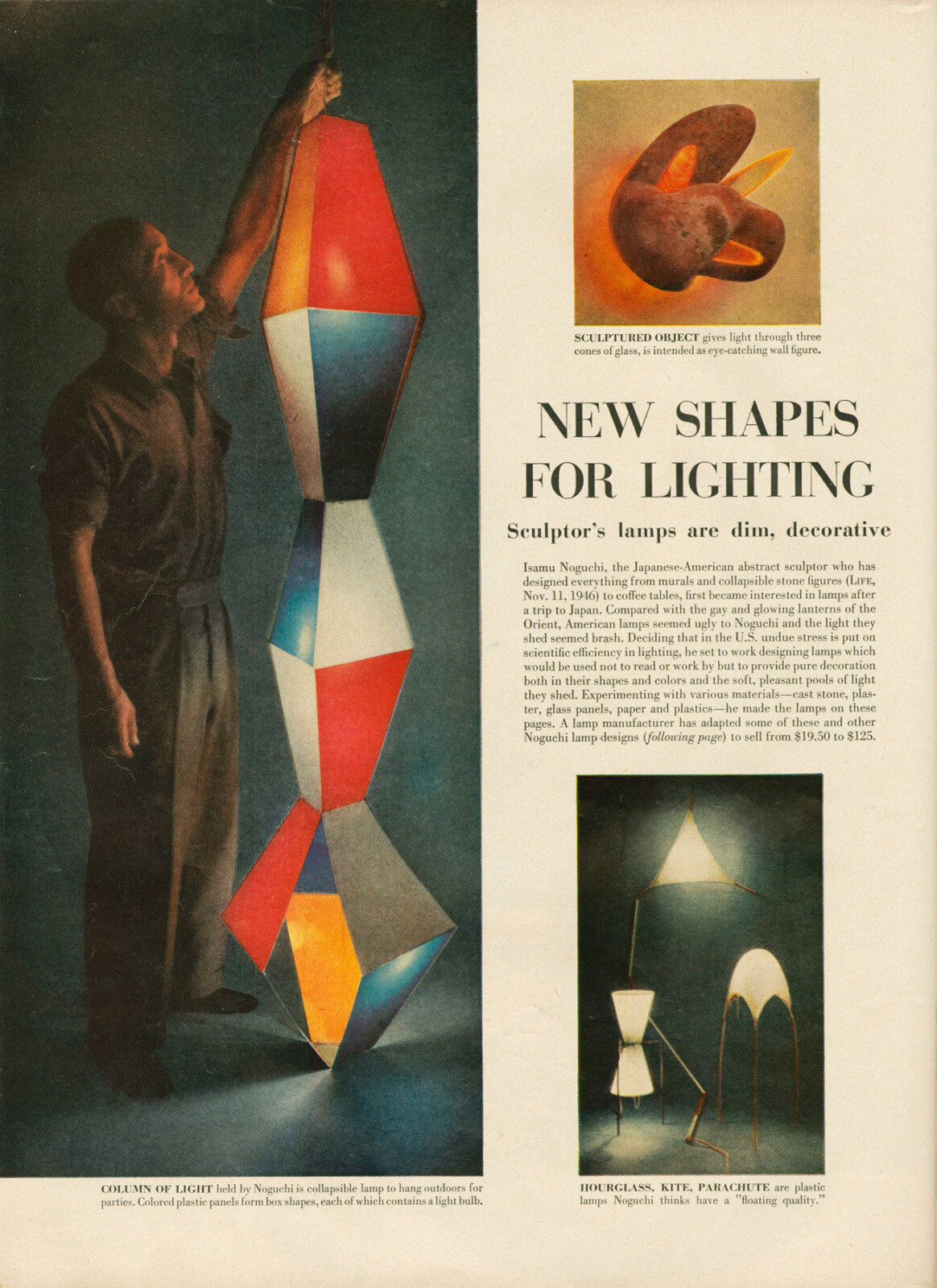

I can’t remember the exact interview, but Braindead’s Kyle Ng once said that he finds the predominant idea of “high-grade” interior design centered around an Eames Lounge Chair and a George Nelson bench super boring. He complained that everybody seems to have the same stuff once a certain income level is attained instead of using those resources to experiment a little and develop personal taste. While the mentioned objects definitely are very well designed and can be ascribed a “classic” status, he has a point. One could make a similar argument about Isamu Noguchi’s “light sculpture” series (- more so, about his glass coffee table even). And although Akari has been very omnipresent itself, and in the form of several knock-off iterations and IKEA paper lamps, I can’t help but be fascinated by them every time they show up somewhere. For example, in one of my favorite NIGO editorials in issue #34 of Relax magazine or a home story on Raf Simons’ house in Antwerp. The Belgian designer once stated that he thinks they are “gentle and modest but really a stroke of genius”. Charles and Ray Eames prominently placed Akari in their famous Case Study House as well. Rumor has it that once the original paper shades wore out, the Eames replaced them with knock-offs on top of the original bases though. And when Tom Sachs held his Tea Ceremony exhibition in the Noguchi Museum in New York in 2016, of course, he scribbled on some Akari to sell them as editions.

Isamu Noguchi was a sculptor before anything else. He declared that “everything is sculpture” and spent his life exploring the limits of the definition, breaking it, and reassembling it according to his beliefs and ideas - sculpting it. Naturally, he believed that light, immaterial and weightless as it is, had the potential to expand his sculpture practice once he came across Japanese chōchin while traveling through the town of Gifu in 1951. These paper lanterns are traditionally illuminated with candles. They are used during several Japanese rituals and festivities as well as for decorating restaurants or shops. Many of them are handmade utilizing high-quality washi paper produced from mulberry bark. Gifu was once the major producer of chōchin in Japan but lost large market shares even before World War II, once cheaper production methods spread in Japan as well as internationally. So when the town’s mayor was introduced to Noguchi in 1951, he pleaded to him to help revitalize Gifu’s chōchin industry while offering him a commission.

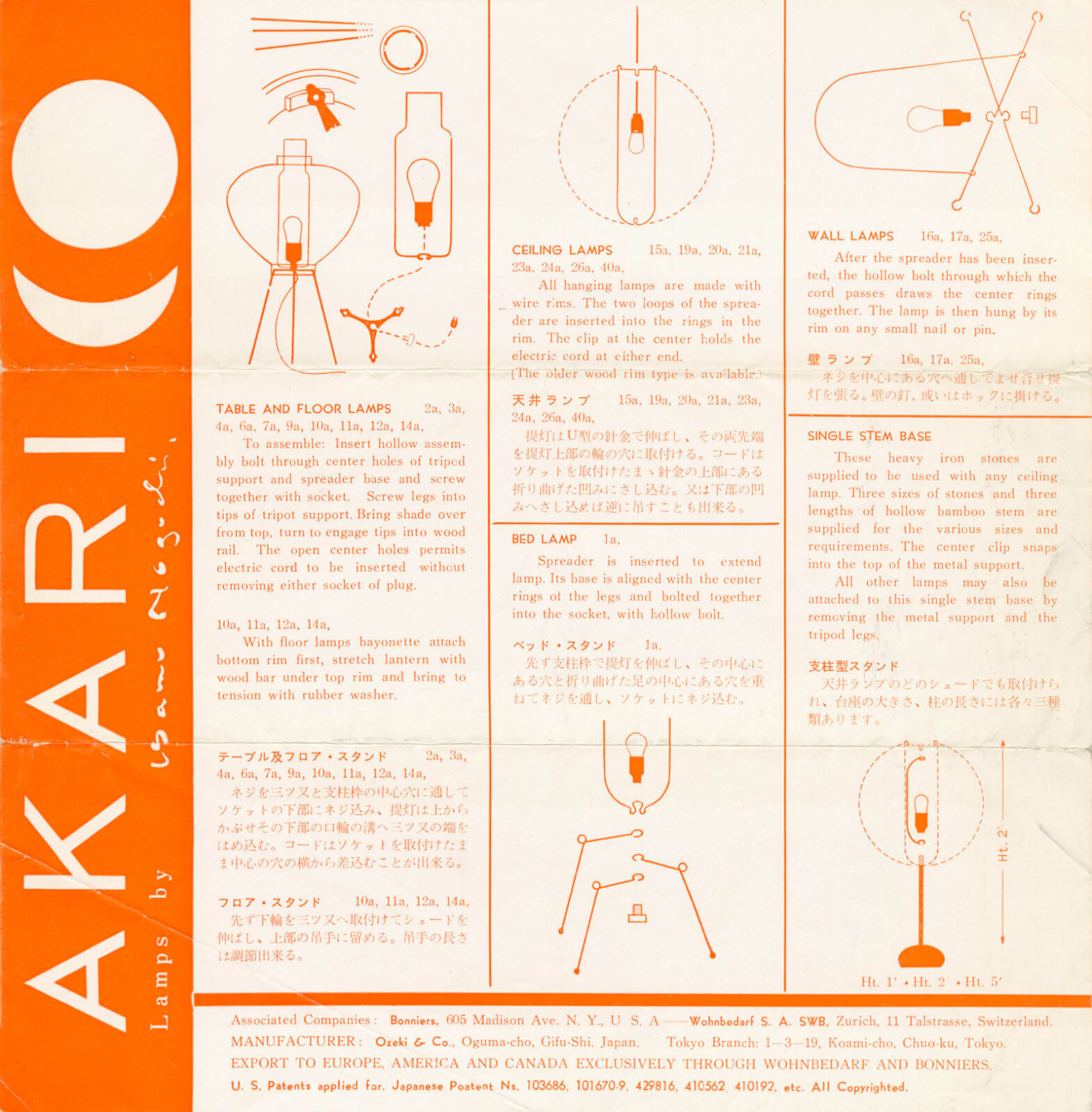

The designer came up with ideas for two new prototypes overnight. A local newspaper described them as “deformed” in an article the following day. Besides challenging the shape norms of the lanterns, he also decided to substitute the traditional candle with a lightbulb as the illuminating element that instantly modernized the whole object. Shortly after, Noguchi formed a partnership with Gifu’s Ozeki Jishichi Shoten (today Ozeki & Co., Ltd.). The manufactory was founded in 1891 and had remained one of the industry’s last survivors. They would oversee the construction of the wooden molds that Noguchi’s creation would be assembled ontop on using washi paper. The durable paper itself presumably held a great appeal for the sculptor because it enabled him to experiment with plasticity and various shapes. Under Noguchi’s direction, the chōchin paper lanterns were transformed into desirable, electrified, and contemporary objects to elevate a home.

““The harshness of electricity is thus transformed through the magic of paper back to the light of our origin – the sun – so that its warmth may continue to fill our rooms at night.””

Akari Light Sculptures logo.

Source: Vitra

Aptly, he named his light sculptures Akari. The Japanese term means ‘light,’ in terms of illumination as well as weightlessness which can be seen as a reference to the collapsible construction of the lanterns. This trait meant the sculptures could be stored and shipped while packaged in a flat box before being unpacked and installed in a home - taking form, allowing the buyer to slightly part in the sculpting process. This play on the relationship between material and immaterial was a central feature in Noguchi’s body of work and was emphasized in Akari as well.

Akari manufacturing process.

Source: The Method Case

Today, the shades for Akari are still meticulously handcrafted in the Ozeki workshop in Gifu. In the first step, bamboo rods are stretched across the original wooden forms designed by Noguchi to create a framework for the object's shape. Then, the washi paper is cut into strips to fit the size and shape of the lamp before being glued to the bamboo skeleton. After the glue has dried, the wooden form is removed, and the shade can be folded to be packed for shipping or storage in flat boxes.

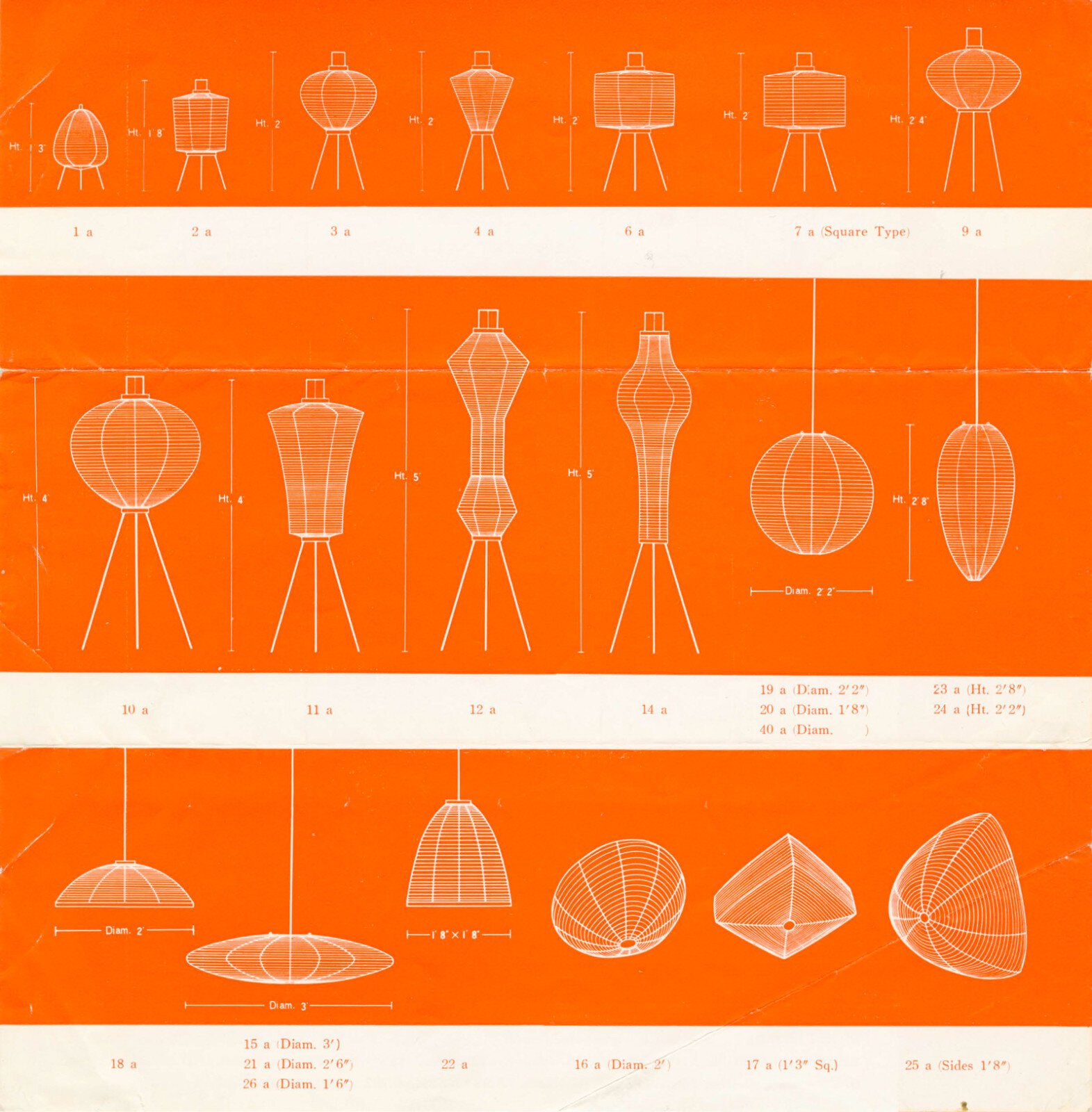

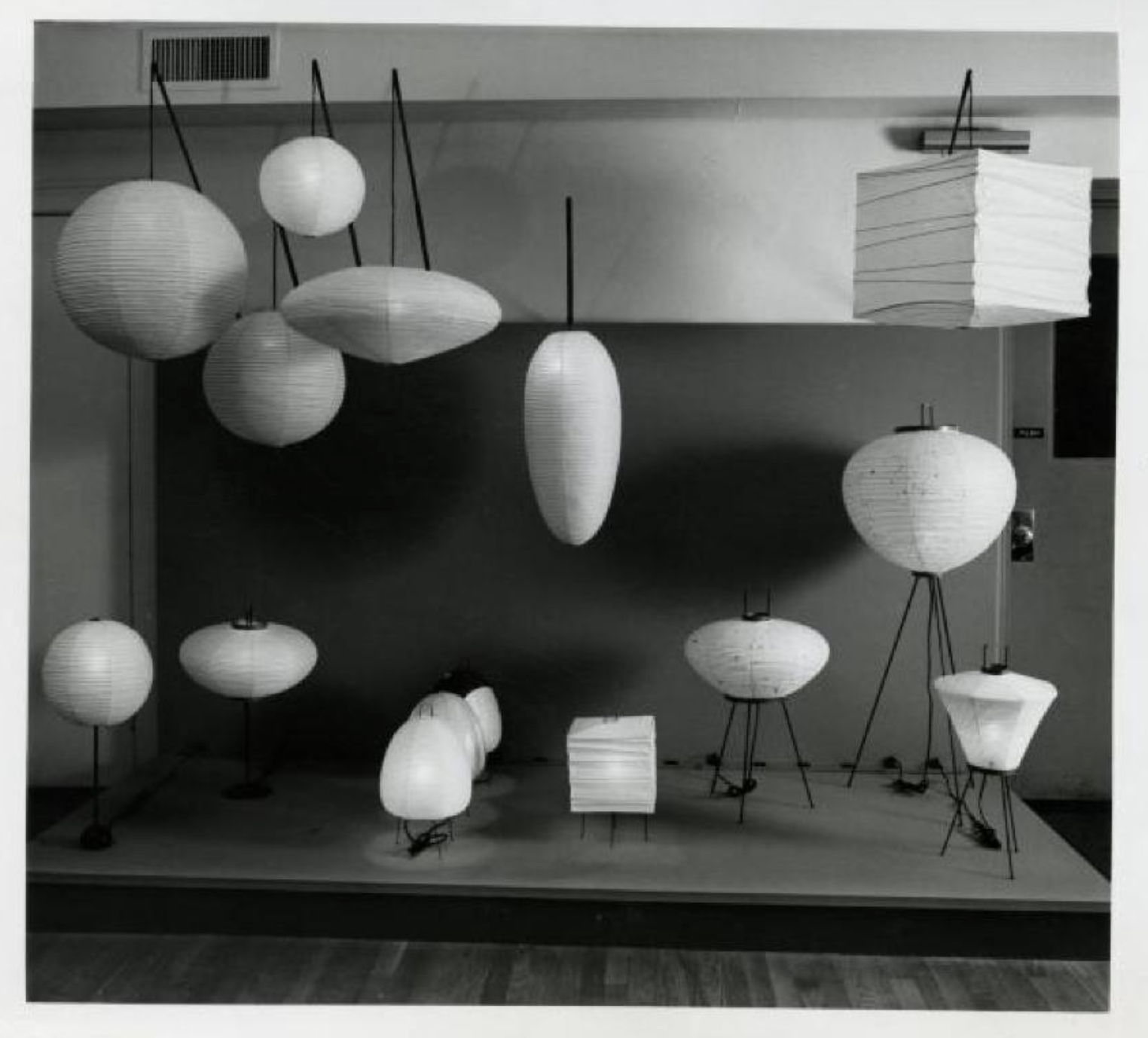

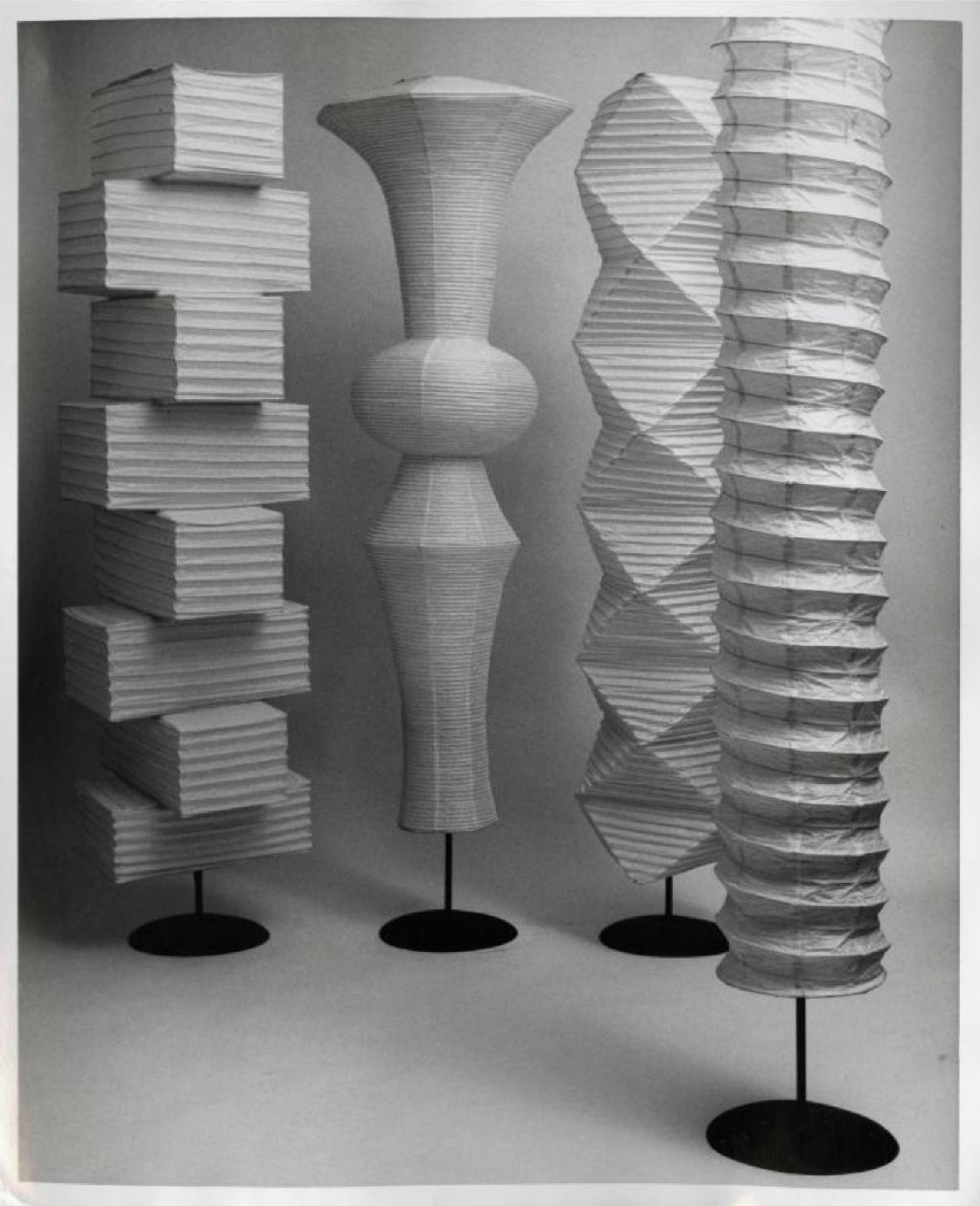

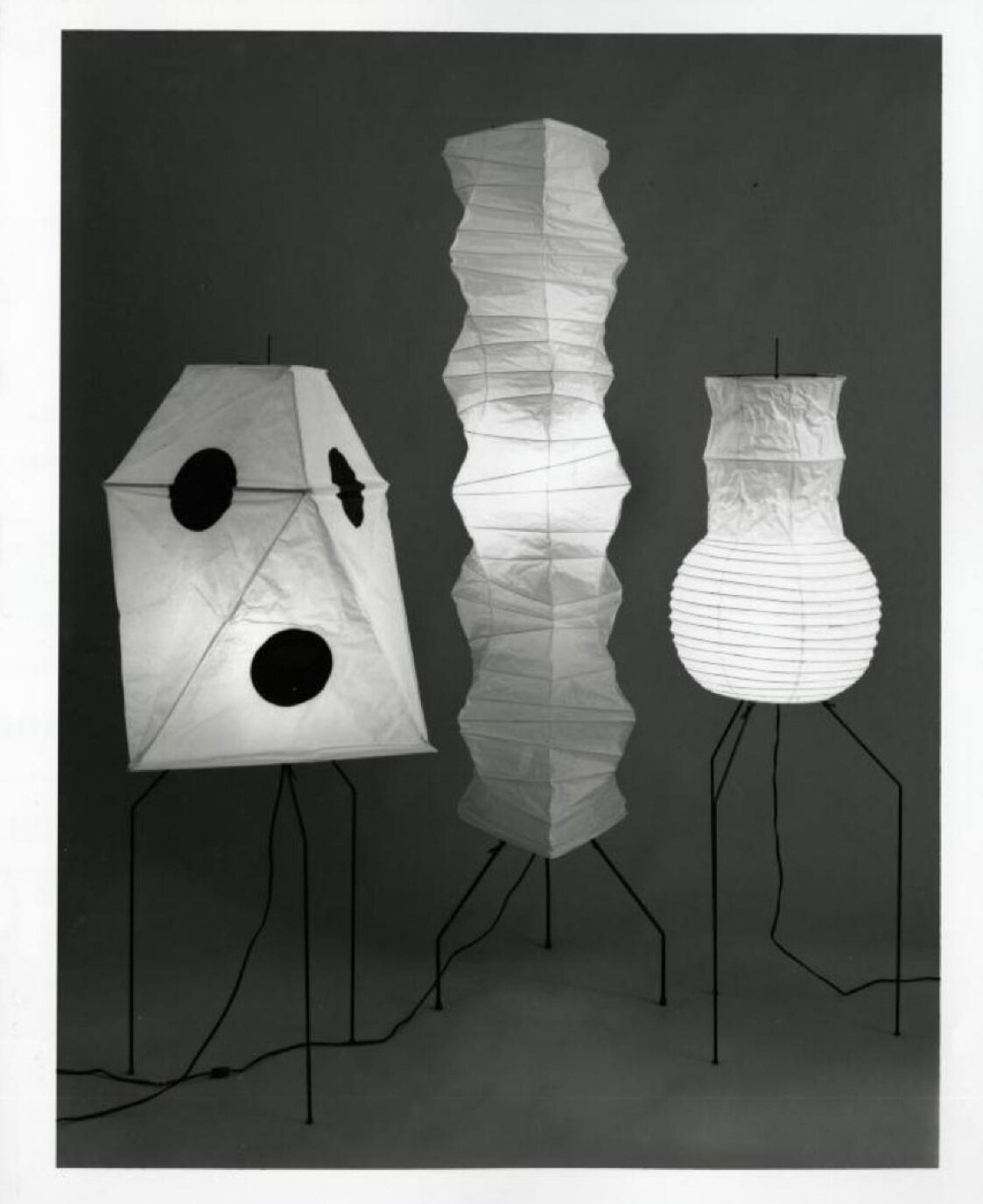

Over the years Noguchi created Akari in various shade forms - globular, asymmetrical, or geometric - and designed them for different lamp bases. Some dangle from the ceiling, while others balance on quite spindly legs. Originally, he intended for all of the series to function as a modular system, so consumers could match the shades with different types of bases. Later, this idea was disregarded for production reasons and because Noguchi wanted to act more freely in building new shapes without being restricted to a set system. Noguchi continued to visit Gifu on most of his trips through Japan and added new iterations to the extensive Akari catalog (over 100 in total), until he died in 1988. The fact that the light sculptures remain in production even 30 years after Noguchi passed, is a measure of his precise vision with a combination of Akari’s novelty (at the time - today: ubiquitous maybe), usefulness, simplicity, and timeless quality.

““When Noguchi was alive, Akari was a living, breathing, changing thing, but when he died, all the innovation stopped.””

Akari promotional image. Circa 1984.

Source: Noguchi Museum Archive

One reason why Noguchi kept expanding the model selection for Akari, was to stay one step ahead of knock-offs and imitations. Because of their similarity to traditional Japanese paper lanterns, he could not patent the designs of his shades. So he decided to patent every other possible Akari component. That includes his designs for bases and frames, for which Noguchi earned five American patents and 31 Japanese patents in total. The suspicion of copycats as well as “big furniture” trying to capitalize on his creations was apparently not too far-fetched. According to Dakin Hart, there is evidence that representatives of IKEA had approached the sculptor with an inquiry to license Akari designs. Noguchi refused, but his designs still inspired the likes of several IKEA paper lamps such as HOLMÖ, REGOLIT, or SOLLEFTEÅ. Not to mention all the other cheaper paper lamp versions as well as more high-end options like Issey Miyake’s IN-EI collection for Artemide.

Besides their lasting impact on interior design, Akari also contributed to the ongoing negotiation between art as a unique, almost “sacred” entity and art as a means to touch as many people as possible - via commercialization. For example, in 1986, Isamu Noguchi contributed a giant Akari lamp to the Venice Biennale and received some backlash from the art world for displaying an object which is also being sold as a kind of consumer product in that “pure art” Biennale context. As if he expected the reaction, Noguchi named his exhibition “What Is Sculpture?”. He explained his decision by assessing that in over three decades of the Akari experiments, the light sculptures were perhaps the one long-running project of his career that brought him the most joy. Noguchi also once said admiringly about his creation that “all that you require to start a home are a room, a tatami (mat), and Akari.”

Isamu Noguchi in his Long Island City studio.

Source: NZZ

Sources:

Noguchi Museum

Vitra

The Method Case

Artsy

Fast Company

Architectural Digest

Thumbnail image: Isamu Noguchi among Akari lights.

Source: Twitter