I’ll Remember This

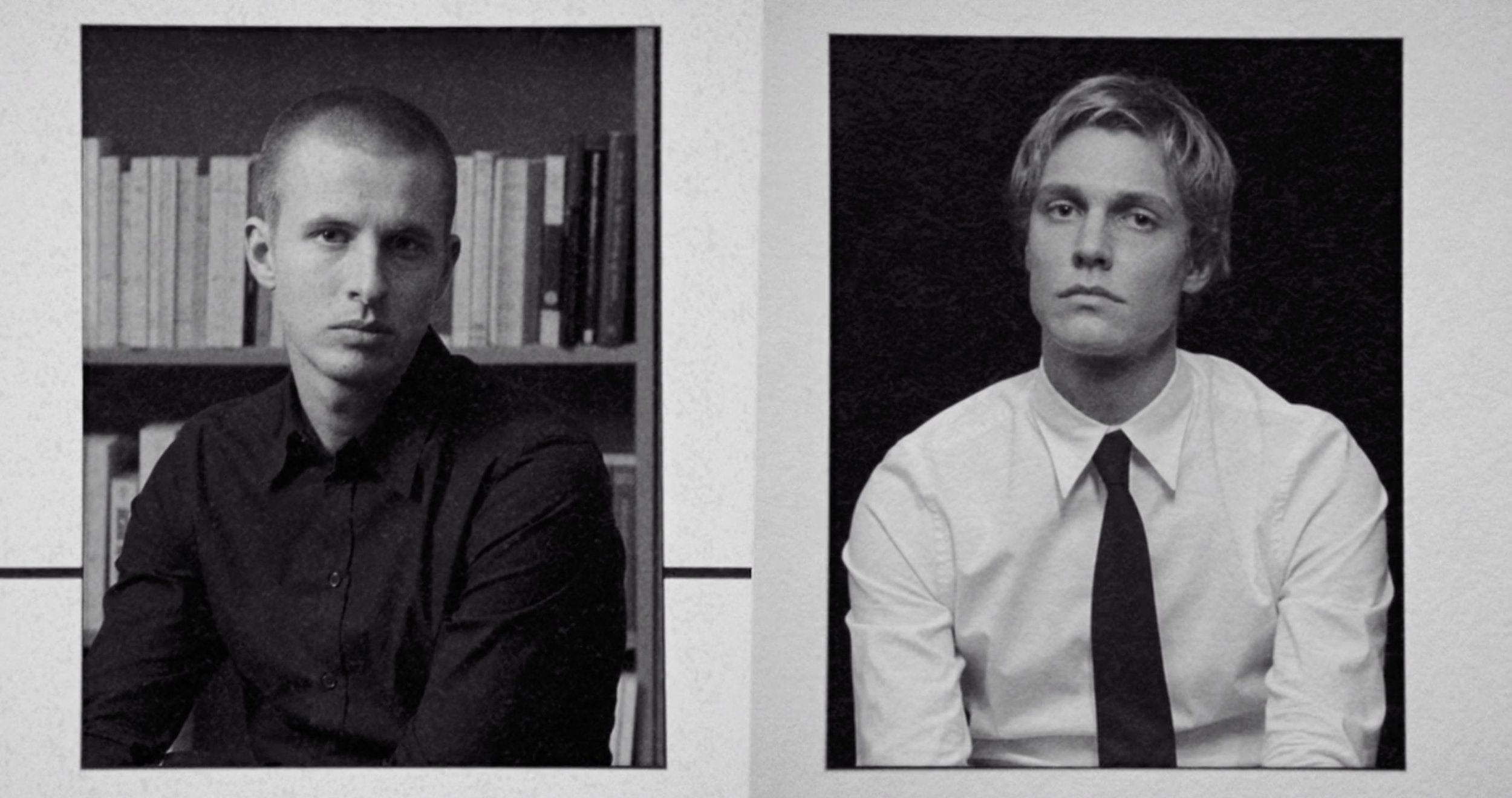

Philip’s office, Saturday morning; from Reprise.

Source: IG

With The Worst Person in the World gaining some global recognition after being hailed as the standout movie of Cannes ‘21, and successively snagging two Oscar nominations, it makes sense to look at the “inofficial trilogy” that is being capped off by [Worst Person] - Joachim Trier’s “Oslo” series.

Spending a lot of his youth seriously skateboarding (he even was “the Norwegian champion” for a time), Trier’s fascination with moviemaking began through watching and filming skate videos. The comment on an Instagram post of a skate video of him and a friend from the mid-90s calling him “the Norwegian Spike Jonze” is not too far-fetched. Not to be confused with his sadistic director namesake Lars von Trier, he has been making short films since 1999 before realizing his first feature in 2006’s Reprise - the first part of the “Oslo Trierlogy”. From the get-go, he focuses on the subjects that define the whole series. Looking inward and dealing with the ambiguous emotions of his characters instead of weaving some twist-heavy plotlines. He predominantly deals with themes around the ambitious pressure of utilizing one’s youth to the fullest while simultaneously achieving something great - mainly as an artist - and the entitled demand to find one’s true self in the process.

What is life worth if you can’t distill it into a transcending artwork? The path to answering that question and some plot developments in the trilogy may feel like cliched tropes. Nonetheless, I would argue that the ends justify the means in this case as they open up the space of thought for more ideas, discussions, and contemplations - admittedly dealing with similar key themes repeatedly. And even though some of the storylines can be predictable at times, Trier manages to orchestrate them with the utmost emotional impact of each situation - weaving in a nihilistic lightness and the heaviness of existence. And sometimes, he finds all those things in simply positioning the inner world of his protagonist against the rather mundane reality they live in.

The characters in the Oslo trilogy mostly find themselves in perpetual cycles of experiences, feelings, drama, and processing all that creatively while time mercilessly passes and youth fades away - many of them portrayed by the great Anders Danielsen Lie. Interestingly, as Trier (and Lie) grew older, the positions of the movies against their world developed, too. Going from great expectations for one’s own artistic ability and the dreams of an epically impactful life growing out of that to the struggles of failure, wasted youth, and mental illness - accepting one’s own mediocrity and inadequacy - before arriving at a more forgiving, soberer, light-hearted, and humanistic perspective on one’s life journey.

Overall, the Oslo trilogy seems to gradually change perspectives on the idea of “nothing really matters” from both ends of the spectrum of conclusions and reactions that realization might send one to. Shifting focus from “the grand scheme of things” to one’s immediate environment, from constructing a delusional vision to confronting and actively sculpting their reality.

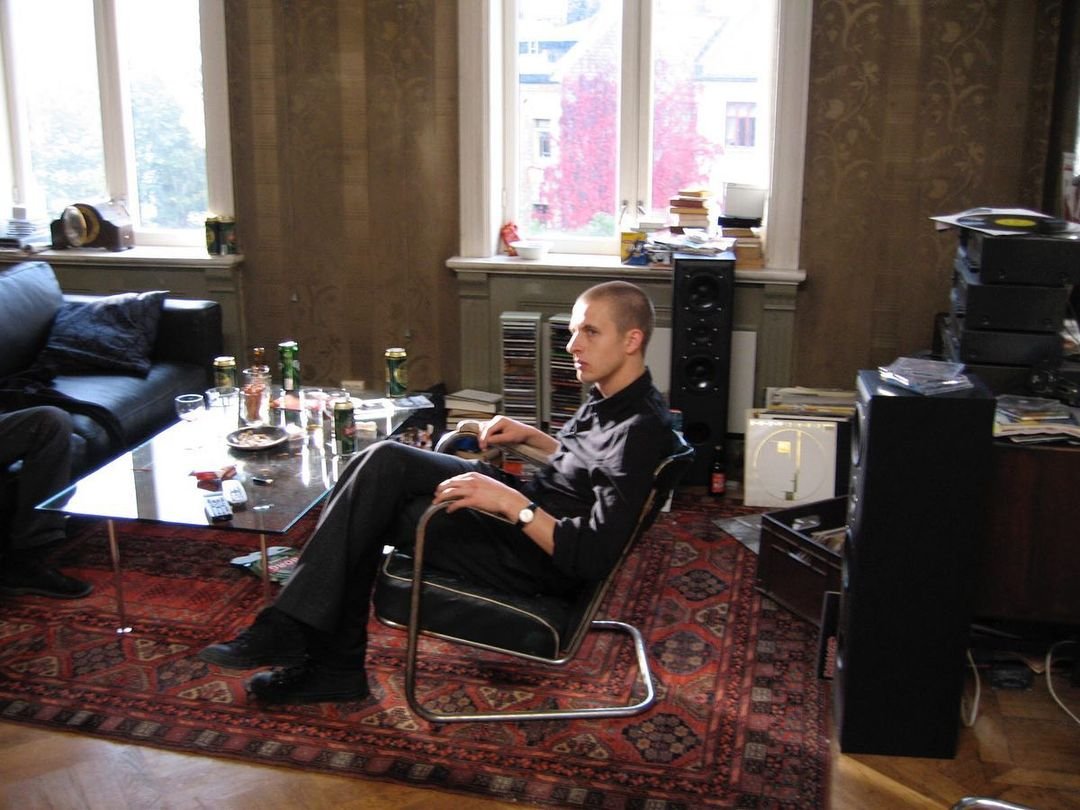

Reprise (2006)

For his debut feature-length film, Trier orchestrates the coming-of-age stories of two young authors contemplating their debut works while maneuvering a complicated friendship-rivalry construct. (Brett Easton Ellis allegedly called it his favorite movie about writers.) One of them is highly talented but also deeply troubled and manic. The other is always searching for approval, ambitious, and in dire need of an identity, desperate to find it in writing - “Erik’s first story took him three months, he later said he wrote it in one night”. One with main character syndrome and the other with a main character complex, if you will - both in their own way narcissistically obsessed with the people they want to become instead of dealing with who they are. In a way, the movie is a work of art about art, and art makes fun of art about art. It deals with “selling out” and the contrast between art and commerce and its (often defeating ironic) co-dependency. Mocking the vanity of artists and the art industry in such a playful attitude with the simultaneous self-awareness of one’s own pretentiousness is not an easy scale to balance.

Roger Ebert wrote that Reprise “seems like a movie written and directed by its [protagonists]” and did not mean it too amicably, I think. While knowing next to nothing about Trier’s personal life, that assertion feels valid though: The group of creative friends going to punk shows, kicking out street lanterns after, and sobering up on Mies Van Der Rohe-like leather couches in a minimalistic industrial apartment filled with books while giving each other shit about opinions and taste, gossiping, and moving forward into increasingly divergent directions. Trier might be playing out multiple of his own youth fantasies in this movie, several storylines he could have seen for his own future. For which should he decide? How possible is it even to actively influence those trajectories?

Oslo, August 31st (2011)

As the title might suggest Oslo, August 31st is one of those “we follow a character for about 24 hours” movies, and what a crushingly impactful one it is. Loosely based on Pierre Drieu La Rochelle’s Le feu follet, it always stays close to its protagonist, who seems disoriented and disconnected from the world around him. Anders (again, played by Anders Danielsen Lee) is on leave for a day from a rehab institution on the premise of a job interview. We see him screw that up in a self-sabotaging manner, but more importantly, he meets with key people from his past on the occasion of being in town again and repeatedly failing to reconnect to (presumably) an ex-partner of his. In those interactions - some nostalgic, some conflicting - it seems like we’re incrementally told what led Anders to drugs in the first place, to rehab, and toward the situation he finds himself in by the end of August. While Reprise brews up a lot of sweet melancholy and shows us the hope to be found in progression, Oslo, August 31st doesn’t gloss over the severity and the scope of suffering that can linger underneath seemingly cushy and mundane life realities. Trier shows us everything we need to know in the first few minutes, but we react just like the people around Anders. In denial, in a selfish attempt to shield ourselves from the inevitable pain creeping up on us. We already know Anders is lost, but don’t allow ourselves to lose hope for him. “All right, all right, he did this, but he won’t do that, right? Right?”.

Although it admittedly can be hard to bear emotionally, there is so much great stuff to be found in this movie and its writing: Ander’s monologue about his parents, his seemingly casual conversation with an old friend turning from sarcastically cynical to drastically alarming within a few moments, the sequence in the café with him overhearing other people’s conversations about their “ordinary lives” reminding him of his nostalgically warm memories of growing up in Oslo, and the glimmer of hope arising from this feeling of connectedness, only for everything to go silent once the café door shuts behind him upon leaving. I remember thinking, “I’ll remember this”.

The Worst Person in the World (2021)

After a two-movie excursion to Hollywood with Louder Than Bombs and Thelma, Trier returned to Oslo after about a decade to finish the trilogy, making “his version of a romantic comedy”. For [Worst Person], Trier opens up his filled-to-the-brim toolbox of stylistic, sometimes literary devices he developed while creating his previous movies. He’s doubling down as a writing filmmaker if that makes sense - arguably closer in spirit to contemporary, melancholic novels (think Sally Rooney for example) than to many contemporary currents in movies. We get a chapter structure (with prologue and epilogue), some party scenes including a surreal, simultaneously hilarious and terrifying, psilocybin-induces mushroom trip, and a magnificent, poetic, and borderline-musical-style time-freeze sequence. Also, a lot of voice-over narration - forget what Brian Cox’s character in Adaption said about that for a second.

Again, Trier takes us along into the emotional world of a character struggling to build a “good life” for themselves - without having a clear vision of how that should manifest exactly. Julie (played by Renate Reinsve - another one of Trier’s phenomenal casting decisions) feels like she is not where she should be, at her age, while rejecting the general idea of age-appropriate touchstones. She wants complete freedom of choice in a vacuum while experiencing choice paralysis in a multi-faceted, complex reality. We follow her as she’s maneuvering herself through this coming-of-age film for adults, through her city, through relationships, through her life - figuring it out.